Ga’an Point

Up at dawn and sit on the balcony, watching the sunrise as people get in the water and enjoy the rest of the park. On our way to breakfast, I notice the $5.14 per gallon sign, but even more eye-catching is what’s written below: Losers sulk; posers talk; winners walk – choose wisely. We chose the Rancho combo from Linda’s Diner so that I could have more than not-so-good boxed pineapple shortbread. The French toast and coffee fill me up.

Hawaiian garden spider, duk duk (hermit crab), yellow garden spider

Caleb is off to complete military chores while I spend the morning exploring. I start at Ga’an Point, where the American Navy landed in July 1944 and cleared the dense groves of coconut palms to build shelters for the more than 6,000 Chamorros released from Japanese concentration camps on the east side of the island. This explains why the interpretive signs are written in English, Chamorro, and Japanese. The next sign at the War in the Pacific National Historical Park warns about the current dangers of the tens of thousands of bombs, grenades, or shells dropped during WWII on a patch of land the size of the city of Chicago.

The views are tropical, the water inviting, the spiders vibrant, and the crabs confident in climbing and socializing. By August 1944, the Seabees had extended runways, and Apra Harbor became a major supply port for the US island-hopping offensive. I take a short walk through the Mount Carmel Catholic Cemetery beside the Agat Unit of the park (there are seven) to appreciate the commonalities and nuances of how different cultures remember their ancestors.

After this, I’m back to the water in a few minutes as I admire the Historic Talaifak Bridge that’s not really that old. The current stone version was built in the 60s, but I would be impressed if the wooden original from the 1780s still stood. On my way to Sella Bay, or to get a look at Mt. Lamlam (the world’s tallest mountain), I spot my first carabao, a swamp-type water buffalo, used for draft work and likely brought to the island by Spanish colonists. I also see a many-lined sun skink that’s better at blending into its surroundings. All the animals seem unconcerned with my presence.

I meet many friendly locals as I make my way from Sella Bay Overlook to Cetti Bay Overlook, both of which are inland, where there is more evidence of the volcanic history in the area. There is also a 1.2-mile hike to a waterfall, which is steep and takes about three hours. I could have ventured in, but as I’ll be meeting Caleb soon, I saved the temptation of going into the forest for driving further south along the island. Evidence of the Spanish colonization, thanks to the ruins of the San Dionisio Church, is still present from 1862.

The first version of the church was erected in 1681 of wood and thatch, but was burned down. The next one was destroyed by a typhoon, and the three after by earthquakes. The Spanish ceded Guam to the US in 1898, so when another earthquake destroyed the latest rebuild in 1902, the structure was never put back together again. This leaves some Spanish stone masonry behind to be grown over by local plants and moss. A few hundred meters away is the Umatac Bridge, built in the 1980s, to resemble the Spanish-era bridge that stood before it, with the railing along the road to match.

This is my turnaround point, and I get to see the new San Dionisio Church, built in 1939 on the site of the Spanish Governor’s summer house. This church has been able to withstand WWII, a series of typhoons, and a massive earthquake in 1993, making it one of the two oldest churches in Guam that is still in use. Instead of holy water, there is a bottle of hand sanitizer by the door, and the six-feet-apart stickers from Covid leading the way between the pews. Some of the nearby houses didn’t fare so well in the natural disasters and were left to be neglected until the next storm can finish the job.

There is a small park that memorializes the 74 Chamorro men out of the 4,000 who served and didn’t make it home. Guam was a medivac station, a forward attack base (temporary base near the front lines), a processing center for over 100,000 refugees, the first US soil for MIAs (missing-in-action), and a “rest and recuperation” area like Bangkok, Tokyo, Taipei, and Honolulu for soldiers and nurses serving multiple tours overseas. For shorter breaks in-country, they were offered Da Nang Beach, Vung Tau, and Saigon. This park was established by the Guam Women’s Club and later adopted by different men’s associations of America and Guam.

carabao

I drive the twenty minutes to base, hang out with Caleb while we wash his laundry, and then he takes me to Piti Guns Trail, another unit of the War in the Pacific NHP, to show me where he went with Smeltkop, a guy who works for him. It’s a wet forest, as everything on this most humid of islands usually is, but we are smart not to slip and slide in flip-flops and lucky to be here on a drier day. We stop at Asan Landing Beach, a third unit, now quiet and imbued with serenity, with a history of a different vibe. We visit the room to eat lunch before continuing on.

church by Piti Guns Trail

Our next stop, the Ritidian Unit of the Guam National Wildlife Refuge, is closed when we get there. The military owns two other units that make up 95% of the park, and their initiative is to preserve the Serianthes nelsonii tree, which only grows on Guam and Rota of the CNMI. The other five percent preserve a pre-Magellan village, a former barrier reef now a cliff, and a nesting site for threatened green sea turtles (which is what we were hoping to see). Instead, we will visit the South Pacific Memorial Peace Park featuring a 50-foot-tall monument of clasped hands to remember the fallen and maintain peace.

Piti Guns Trail

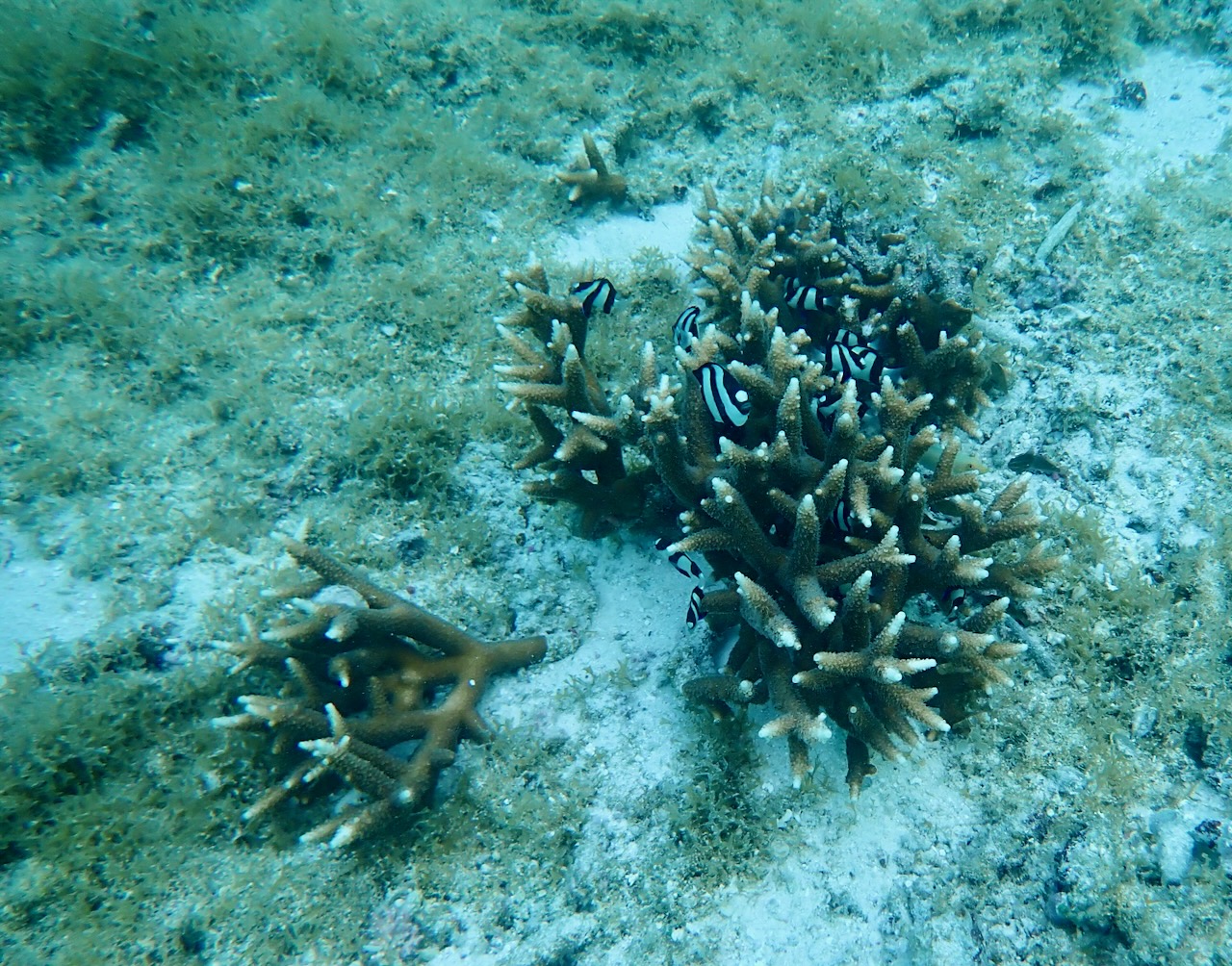

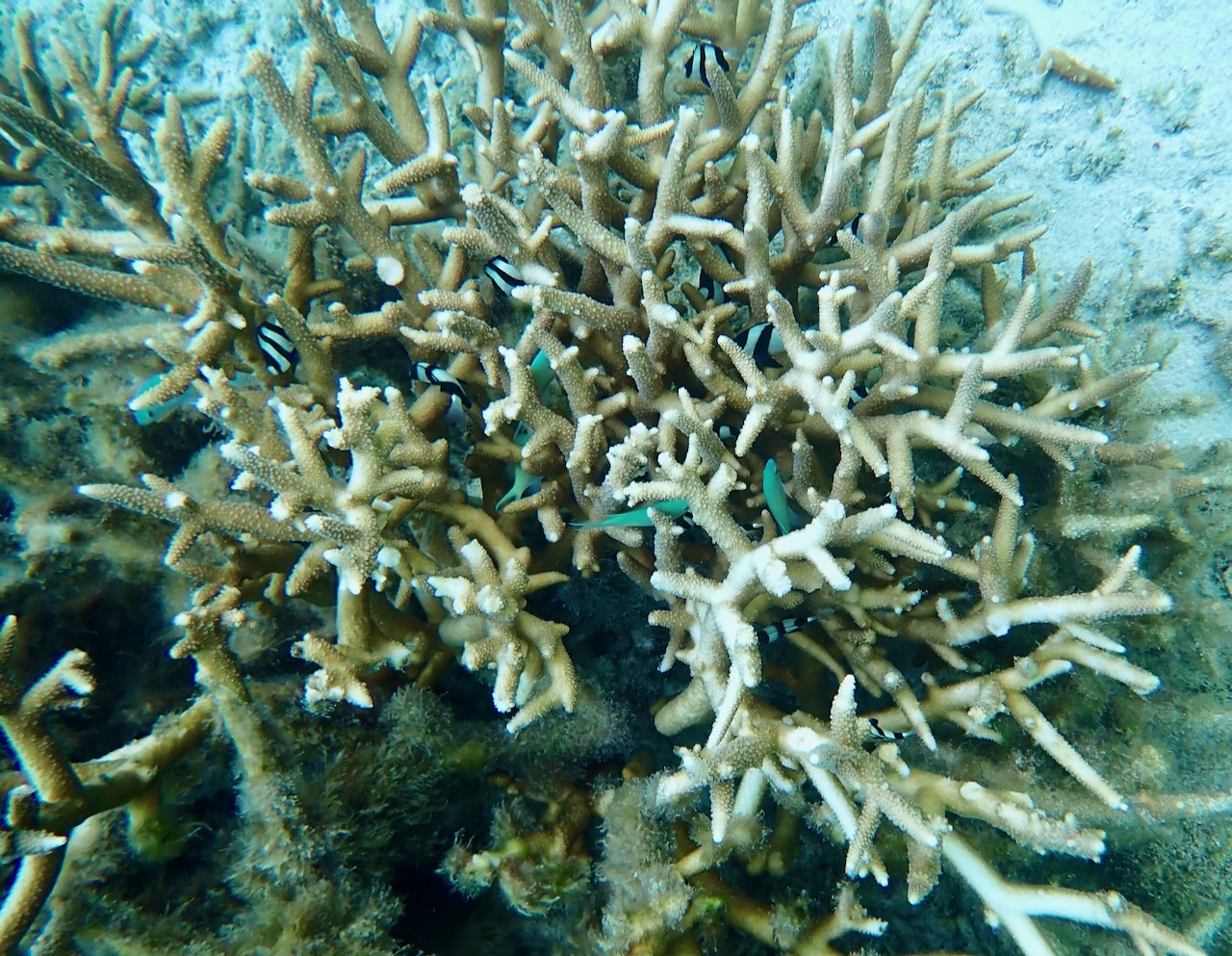

Caleb let me know that places were only open two days a week, and I thought perhaps it was just a scheduling conflict. However, as we attempted to visit the Guam Museum (which opened in 2014), I realized it was us going to these places on the two days a week that they are closed. We change into swim gear back in the room and walk to the calm and shallow bay for over an hour of snorkeling. While face down in the water, I see a snake sea cucumber (usually about seven feet long), banded archerfish (known for shooting down land-based insects), a few orange-spotted filefish (distinct long nose), some sammara squirrelfish (giant low-light eyes), and the majestic Moorish idol (not an angelfish).

where we snorkeled and the 50-foot-tall clasped hands

I also see an unidentifiable white slithering object (either a brown tree snake or banded snake eel), a Picasso triggerfish (able to swim backwards like the eel and knifefish), a four-legged blue sea star (they usually have five), and a raccoon butterflyfish (which are generally aggressive towards lionfish and triggerfish). The walk back to the room is cold, but after a warm shower, we are ready for dinner. Smeltkop has invited us to The Beach Restaurant on Gun Beach, where coconut crabs were more common before being overharvested; hunting them is banned on base, and there are now collection laws in place to protect the remaining population.

We get seated near the bar and live music that the guys have to talk over to discuss work. Smeltkop asks the waiter if “the DJ can turn it down,” instead of requesting to move away from the giant speakers. We are treated to a cloudy yet beautiful sunset, and then go looking for crabs in the dark with no luck. Caleb is more tired than he lets on, but as soon as he sees the bed, there will be no time for reading, just sleep. I have to remember that he worked and had a full day with me. I’m glad and grateful that I’m able to join him on his shorter work trips, as the Navy frowns upon stowaways.