Another early morning, though the sun is already up, we’ve got two of the longest bridges (Lake Pontchartrain Causeway and Atchafalaya Basin Bridge) in the US to cross, with another twenty miles of other elevated roadways over swamps, bayous, and floodplains to get to New Orleans. This city, known as the “Big Easy,” is wet and gray when we arrive, and the streets are empty. The Historic Voodoo Museum is open and full of figurines and paintings that are covered in cigarettes, booze, and money as a tribute to the bringers of good fortune.

Voodoo comes from the people of West Africa. They believe in three levels of spirituality: a distant God, spirits on Earth, and deceased ancestors. Voodoo is the label for the religion, the superstition, and the culture. Marie Laveau is the Queen of Voodoo. She was born two years before the Louisiana Purchase and died two years after New Orleans’ first telephone directory was published. She brought her mulatto heritage (black grandmothers, white grandfathers) into her healing. Her specialty was love, which caused leaders around the world to seek her advice and help.

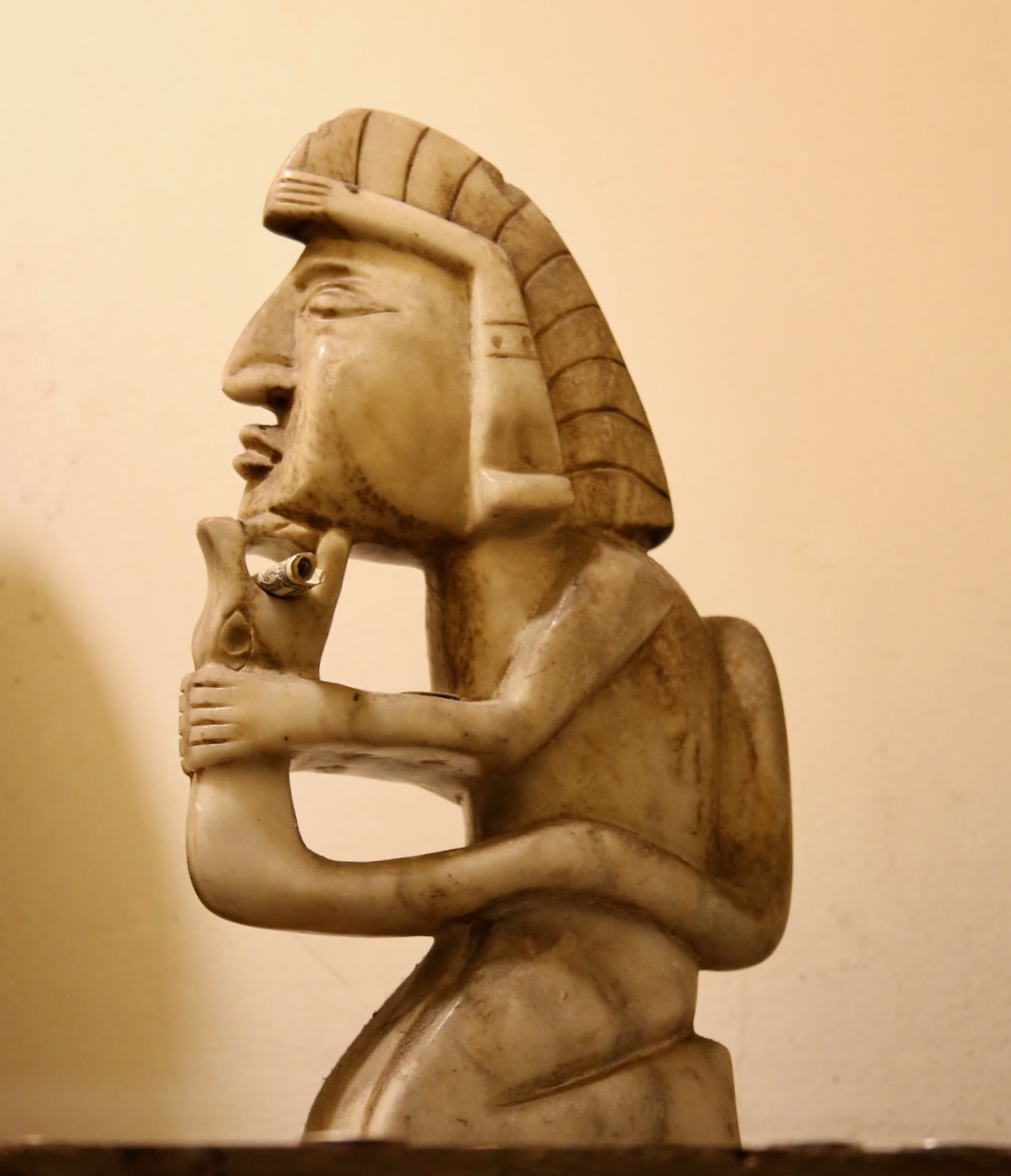

There are many artifacts and treasures in the different rooms. There was a secret society that carried out crimes in the name of personal justice, and today, there is a group that warns kids during Mardi Gras of the fragility of a fleeting life. There are trinkets, skulls, masks, and the most popular piece from Voodoo, the doll, unless you count Hollywood’s use of the zombie. Haiti had a practice of poisoning the chosen few, burying them alive for several hours, and then giving them the antidote. This experience shattered their spirits and made these people easier to dominate.

As we exit the museum, I see modern zombies stumbling about the streets with their drinks in hand. We’re not out long before we find the Jazz National Historical Park that evaded us last time due to a lack of parking. The “Tree of Jazz” is broad and built like a willow. It stands strong on its roots of gospel, ragtime, and military brass and branches out to include blues, swing, bebop, and fusion. The trans-Atlantic slave trade merged African and European music on Caribbean islands, and many of those rhythms continue to be practiced and built upon in New Orleans.

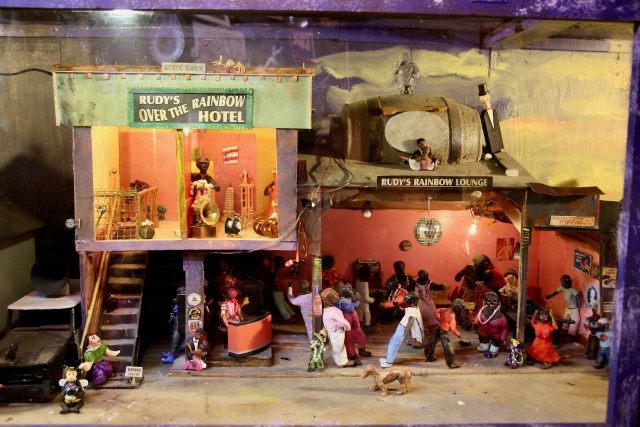

A detour a bit north over the Causeway I mentioned earlier (that’s not needed to access New Orleans from the west) takes us to the Abita Mystery House. It’s a roadside attraction packed with handmade inventions, mini-town dioramas, and collections: bottle caps, stickers, signs, license plates, paintings, bottles, film rolls, arcade games, sunglasses, etc. It’s just one guy, artist John Preble, and his over-friendly cat that claim these oddities, especially the rogue taxidermy with an alligator theme. Just a few minutes away is the Abita Brewing Company. I know their beer Purple Haze, a wheat ale with raspberries, so we take a tour, buy a shirt each, and ask about where to get dinner.

We agree on The Chimes, where I have my second croissant of the day. Mississippi was a sweet hour before we stopped in Alabama, where I picked up homemade F.R.O.G. jam (fig, raspberry, orange, and ginger, which I would later have to leave at the airport) and mosquito bites on my left foot (that I can still see six weeks later). We’re both exhausted trying to get onto IWTC Corry Station, my first command after Chicago in the Navy, and it’s not as accessible at night as it used to be. The camp host is too sweet and offers me a tour of the place that I decline, along with a free bag of ice.